Line-breeding and the coefficient of relationship

Often breeders choose to breed with dogs having common ancestors, with the aim of reproducing consistently a set of desirable morphological or behavioral characteristics. In fact, all dog breeds have developed through a phase of in-breeding among members of a relatively small population. Once a breed is successfully established, still selected lines of dogs are used in the attempt of obtaining specific characters (line-breeding). For a breed of relatively small size, such as FCRs, some level of line-breeding also appears due to a few dogs that have been used many times as stud.

|

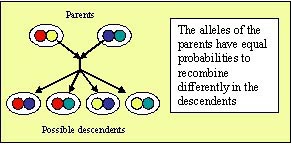

Line-breeding has advantages and disadvantages. Having common ancestors in the parents' lines implies an increase in the probability of finding in the genotype areas of identical alleles (see figures). Organisms that reproduce sexually have their genome formed by pairs of alleles, with the case of of different alleles, heterozygosity, more frequent than that of equal ones, homozygosity. (The incidence of homozygosity in dogs is further discussed below.) In general, this is an advantage, since undesired or pathological characters that may be present in a single allele are typically recessive, i.e. not active, in face of a complementary allele of different nature and generally healthy. |

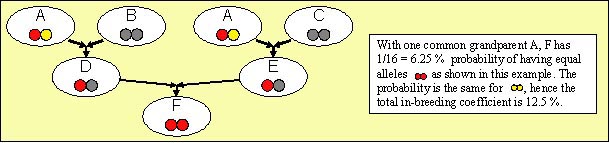

| The presence of common ancestors in the lines of father and mother increases the probability of homozygosity. If the common ancestor is a carrier of a recessive genetic disorder (both alleles should be involved in order to be affected by the disease), the chance of the progeny being affected is increased compared to offsprings from unrelated lines. |

|

In-breeding coefficients in our dogs and homozigosity in dogs (last update: 28/05/2011)